Kingscape

In addition to palaces, royal courts and imperial castles, the medieval royal landscape also included cathedrals and imperial abbeys, which were not uniformly distributed throughout the empire and which were frequented relatively evenly by royal sojourns. With the election of Henry I as king in Fritzlar in 919, the royal landscape shifted to the Saxon region. Here the ducal family of the Liudolfingers, from which Henry descended, had extensive possessions. Together with the Carolingian imperial property that fell to him when he was elected king, he developed the Harz-Elbe-Saale-Unstrut region into a new royal landscape.

The early days of the Quedlinburg Collegiate Hill

Today's Schlossberg, a substructure with fillings, is 100 m long and 50 m wide. Quedlinburg is first mentioned in a document of Henry I dated 22 April 922, which was issued for the Corvey monastery (D H I 3).

The area of the Schlossberg was already settled at an earlier time. Archaeological investigations have uncovered traces from the Ice Age (flint blades), the Neolithic Age (cellar pits, vessels of the Linear and Corded Pottery), the Bronze Age (a stone wall with clay packing as a rampart as well as sherds, vessels and living pits) and a stone dwelling dating from around 500.

The palace of Henry I

The location and appearance of the palatinate has been and still is the subject of much debate in research. According to the document of Henry I from 922, it can be assumed that it was erected in a royal court(villa). Where exactly this was located is not known. It can be assumed that the farm belonging to the palatinate was located in the area of today's Wipertikirche. Here there was sufficient space for the necessary arable and pasture land. The other palace buildings (palace chapel, palas and residential buildings) are assumed to have been on the castle hill.

With the foundation of the monastery in 936 and the settlement of a convent of ladies under the leadership of Queen Mathilde, the palace was moved to the area of the farmyard.

The first buildings on the castle hill - palas and palatine chapel

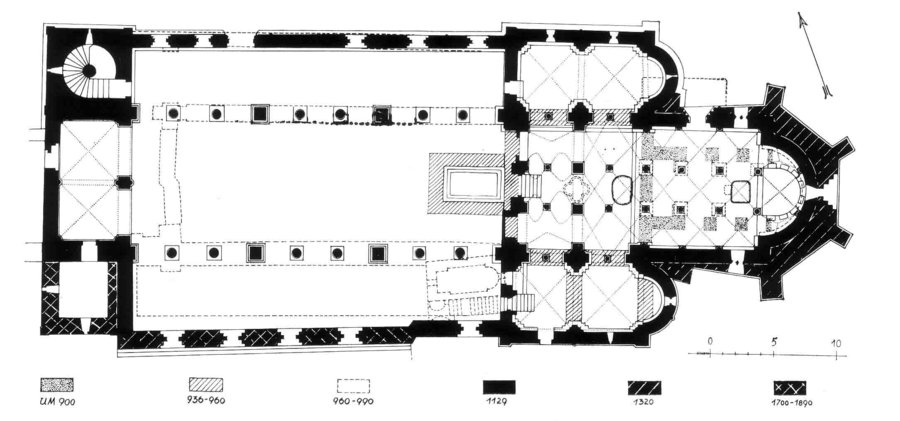

During archaeological investigations on the Schlossberg, traces of two separate buildings were found: The first, a church building, is dated to the first third of the 10th century. It was a small, three-aisled church building with a square ground plan and an eastern apse, which was once located in the eastern area of the present crypt. To the west of this church, which measured about 10 x 10 m, was a 27.5 m long rectangular hall. It can be assumed that this building was the first church on the Schlossberg. Henry I was buried in this small church in 936. The so-called palas (government hall) of the former Quedlinburg Palatinate could then have been connected to this as an independent building.

The extension of the Palatine Chapel to the collegiate church - the first extension (Building 2)

With the elevation of the Palatine Chapel to a collegiate church in 936, the first church building not only experienced the establishment of a ladies' convent, but the first structural changes will also have been made. In the time of the queen dowager Mathilde, to whom the first structural changes can be attributed, the so-called Confessio was carved into the rock below the altar in the east apse. The exact function of this room can no longer be clearly traced due to its special design (semicircular and provided with niches) and dimensions. It is assumed that, on the one hand, the niches were once provided with relics and that, on the other hand, the proximity of these to the deceased was intended to ensure the intercession of the saints with God. In the 19th century, it was assumed that the Confessio was a crypt under the main altar and, moreover, that this enclosure offered visitors the opportunity to take a look into Henry's tomb.

"When she [Abbess Mathilde] saw that this church [...] was too narrow for the mass of the people streaming in and in proportion to its great importance, she endeavoured [...] to put there a temple of wider and higher construction [...]." This description in the Quedlinburg Annals for the year 997 indicates that there were structural changes to the church interior under Abbess Mathilde of Quedlinburg. The results of the archaeological investigations indicate an extension of the Palatine Chapel and the first collegiate church by the addition of a transverse wing in the western area. Presumably, a connection was also made to the hall building located to the west. This resulted in an extension of the church interior to 52 m.

The collegiate church of Abbess Adelheid I (Building 3)

The Quedlinburg annals report on the consecration of the collegiate church in 1021, at which the imperial couple Heinrich II and Kunigunde were present. Whether the consecration was due to completed building work or for another reason cannot be inferred from the medieval sources.

Archaeological investigations have shown that the nave and transept were extended again at a later date (after the year 1000). With its completion, the collegiate church then had its present dimensions. The area of the first collegiate church building was covered with an over-church and thus already acquired the character of a crypt.

The reconstruction of the collegiate church (Building 4 ?)

The annalist Lampert von Hersfeld wrote about the year 1070: "The venerable minster in Quedlinburg caught firewith all its outbuildings [...] and was completely incinerated. " Previous archaeological investigations in the Schlossberg area yielded no evidence of fire traces in this area. Whether the fire was related to individual parts of the building or the entire Schlossberg cannot be conclusively determined. What is certain is that the church was consecrated again in 1129 and this church still exists today.

Burial place of Henry I in Quedlinburg

Saxon sacral topography in the 9th to 11th centuries / foundation of women's communities

In medieval Saxony, from the 9th to the 11th century, noble families founded almost exclusively ecclesiastical women's communities and endowed them with corresponding economic property. These foundations were a sign of social as well as political position and served to consolidate power and representation. The most important task of these spiritual communities was the care of the memoria as well as the salvation of the founding family, their relatives and friends. In addition, family foundations served both as a place of retreat for widows of the family and for the education of noble daughters.

Founding of the Damenstift in Quedlinburg

On September 16, 929, King Heinrich I bequeathed the villages of Quedlinburg, Pöhlde, Nordhausen, Grone and Duderstadt as wittum to his second wife Mathilde. According to the descriptions of the queen's life, the ruling couple is said to have intended to found a spiritual institution in Quedlinburg, the king's favourite palace, which was to be staffed with nuns from the Wendhausen (Thale) monastery. With this foundation, Henry turned away from the actual family burial place in Gandersheim. This can be seen as a conscious sign of the new and at the same time better social and political position of the Liudolfing family. Heinrich himself was only able to obtain the consent of the Wendhausen abbess at a court day in Erfurt, but he died before the Quedlinburg Palatine Chapel was elevated to a ladies' foundation on July 2, 936 in Memleben. The king's body was transferred to Quedlinburg and buried there in front of the altar.

On September 13, 936, Henry I's son, King Otto the Great, confirmed the foundation and property rights of the Quedlinburg Damenstift, which had been advanced by his father and mother. At the same time he placed it under direct royal protection and in 948 under papal protection. With the words "[...] pro remedio animae nostrae atque parentum successorumque nostrorum [...]" (D O I 1) Otto defines the task of the ecclesiastical women's community: it was to care for the salvation of the souls of his ancestors and successors. Thus the care of the memoria received the highest primacy. The leadership of this women's community was taken over by the queen dowager Mathilde herself. She presided over the community for 32 years. In 966, the eleven-year-old daughter of Otto the Great and granddaughter of Henry I became the first abbess of the Quedlinburg convent. Like the queen dowager, she also bore the name Mathilde. Until the death of her grandmother, the young abbess will have been instructed in the essential tasks of the spiritual community and prepared for the office of abbess. With the death of the queen dowager on March 14, 968, she then took over the leadership of the Quedlinburg convent of ladies.

The abbesses as spiritual and secular mistresses

The importance of the Quedlinburg convent becomes clear not only in its status as an imperial and secular institution and as a memorial to the first Ottonian king, but also in the role of the abbesses in the secular and ecclesiastical events of their time.

As abbesses, they not only presided over their own spiritual community, but were also representatives of the royal and imperial dynasties, as they came from these families. First and foremost, they represented the affairs of the Quedlinburg convent. Thus the abbesses founded monasteries, e.g. St. Marien on the Münzenberg in Quedlinburg or St. Michaelis in Blankenburg, and increased the possessions of the convent by acquiring various estates. But they were also active in the political field. For example, Abbess Mathilde was the imperial administrator for her nephew Otto III, who was in Italy at the time, from 997 to 999, and not only held a court day in Derenburg, but also presided over it. These tasks were otherwise only given to men from the ruler's family. Mathilde took on the political role of a domina imperialis (secular mistress), travelling with the rulers through the empire and assisting them. But subsequent abbesses also took their place in the political world: for example, they took sides in disputes over succession to the throne or acted as mediating parties. The Quedlinburg abbess even had a seat and voting rights in the Imperial Diet until the dissolution of the monastery in 1804. Thus these clerical women also stood up to the nobility as secular mistresses. The resulting self-confidence is still represented today by the tombstones of these women in the crypt of the collegiate church and the extension to the so-called Quedlinburg Castle.

Memoria

The medieval form of memoria (Latin for remembrance, memory) has its origins in the pagan-ancient custom of the funeral banquet, i.e. a memorial banquet was held at the grave of the dead person by the family and relatives and the dead person was perceived as a participant. Thus, gifts were offered to him, a drink was poured into the grave and offerings were made to the gods. These were charitable services.

This form of the funerary meal at the grave of the deceased changed in Christian usage to a Eucharistic meal celebration (liturgical thanksgiving), in which the intercession for the deceased took place in the service of the word. This consisted of two parts: the intercession (lat. oratio fidelium), which usually took place without the recitation of names, and the celebration of the Lord's Supper with the naming of names. This way of remembering the deceased also included living but absent persons. The names of persons to be commemorated were recorded in so-called necrologies (register of the dead) or libri vitae (book of the living). These in turn were based on martyrologies (lists of martyrs and saints) and calendars (lists of church feast and memorial days). They extended the structure of the commemoration of the dead to include the commemoration of saints.

The adoption of the pagan-ancient feast for the dead was accompanied by the adoption of the day of remembrance of the dead: this was celebrated on the 3rd, 7th (9th) and 30th (40th) day after death, as well as the anniversary on which, according to custom, a mass was held for the dead as a votive mass.

The naming of the dead made them present and reflected the concern for the salvation of the soul, which was an important part of medieval society. Forgetting was to be overcome in this way.

The task of memoria for the deceased and the living was entrusted to ecclesiastical institutions. In order to fulfil this important task, these institutions received donations to secure their existence (e.g. land, candles, food, clothing etc.). This created a mutual benefit principle in which the material gift supported the community and the spiritual counter-gift (prayer and intercession) strengthened the private person. Thus care was taken both for one's own salvation and that of others, in which the charitable thought finds expression. Even the poor could act as intercessors for the salvation of souls.

Picture credits

Jacobsen, Werner, On the early history of the collegiate church of Quedlinburg, in: Denkmalkunde und Denkmalpflege 63 (1995), pp. 63 - 72.

References

The Annales Qudlinburgenses, ed. by Martina Giese, Hannover 2004 (MGH Script. rer. Germ. 72)

Translation: Die Jahrbücher von Quedlinburg, translated by Eduard Winkelmann, Berlin 1862 (Die Geschichtschreiber der deutschen Vorzeit, 10th century, vol. 9)

Lamperti monachi Hersfeldensis Opera, ed. by Oswald Holder-Egger, Hannover / Leipzig 1894, p. 112 (MGH SS rer. Germ. 38)

Lampert von Hersfeld, Annalen, newly translated by Adolf Schmidt and explained by Wolfgang Dietrich Fritz, with an updated bibliography by Gerd Althoff, 4th biographically updated edition 2011, p. 125 (Freiherr-vom-Stein-Gedächtnisausgabe 13).

The biographies of Queen Mathilde. Vita Mathildis reginae antiquior - Vita Mathildis reginae posterior, ed. Bernd Schütte, Hannover 1994 (MGH Script. rer. Germ. 66).

Translation: Das Leben der Königin Mathilde, ed. Philipp Jaffé, reprint of the 2nd edition of 1891, 1st edition, Paderborn 2011 (Die Geschichtsschreiber der deutschen Vorzeit, 10th century vol. 4).

The charters of Henry I, ed. Theodor von Sickel, Hannover 1884 (MGH Diplomata regum et imperatorum Germaniae 1).

The charters of Otto I, ed. Theodor von Sickel, Hannover 1884 (MGH Diplomata regum et imperatorum Germaniae 1)

References

Althoff, Gerd, Gandersheim and Quedlinburg. Ottonian women's monasteries as centres of rule and tradition, in: FMSt 25 (1991), pp. 123 - 144.

Bodarwé, Katrinette, Sanctimoniales litteratae. Schriftlichkeit und Bildung in den ottonischen Frauenkommunitäten Gandersheim, Essen und Quedlinburg, Münster 2004 (= Quellen und Studien, vol. 10).

Bulach, Doris, Quedlinburg als Gedächtnisort der Ottonen. From the foundation of the monastery to the present, in: ZfG 48 (2000), H 1, S. 103 - 118

Fleckenstein, Josef, Pfalz und Stift Quedlinburg. Zum Problem ihrer Zuordnung unter den Ottonen, Göttingen 1992 (= Nachrichten der Akademie der Wissenschaften in Göttingen. I. philosophical-historical class, vol. 1992 no. 2).

Giesau, Hermann, Die Grabungen auf dem Schlossberg in Quedlinburg. The historical period, in: Deutsche Kunst und Denkmalpflege 1939/1940, pp. 104 - 115

Grimm, Paul, Stand und Aufgaben der archäologischen Pfalzenforschung. In the districts of Halle and Magdeburg, Berlin 1961 (= Deutsche Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Berlin,

Lectures and Papers, vol. 71)

Hase, Conrad Wilhelm / Quast, Ferdinand von, The graves in the castle church at Quedlinburg, Quedlinburg 1877

Jacobsen, Werner, Zur Frühgeschichte der Quedlinburger Stiftskirche, in: Reupert, Ute (ed.), Denkmalkunde und Denkmalpflege. Knowledge and Work. Studies in honour of Heinrich Magirius on the occasion of his 60th birthday on February 1, 1994, Dresden 1995, pp. 63 - 72.

Lehmann, Edgar, Die "Confessio" in der Servatiuskirche zu Quedlinburg, in: Möbius, Friedrich / Schubert, Ernst (eds.), Skulptur des Mittelalters. Function and Form, Weimar 1987, pp. 8 - 26.

Leopold, Gerhard, The collegiate church of Queen Mathilde in Quedlinburg. A preliminary report on the foundation building of the Damenstift, in: FMSt 25 (1991), pp. 145 - 170 incl. plates VI - XI

Leopold, Gerhard, Archaeological excavations at sites of the Ottonian rulers (Quedlinburg, Memleben, Magdeburg), in: Althoff, Gerd / Schubert, Ernst (eds.), Herrschaftsrepräsentation im ottonischen Sachsen, Sigmaringen 1998, pp. 33 - 76

Leopold, Gerhard, The Ottonian churches of St. Servatii, St. Wiperti and St. Marien in Quedlinburg. Summary of archaeological and architectural research from 1936 to 2001, Halle (Saale) 2010 (= Arbeitsbericht 10).

Ludowici, Babette, Quedlinburg vor den Ottonen: Attempting an Early Topography of Power, in: FMSt 49 (2015), pp. 91 - 104.

Moddelmog, Claudia, Royal foundations of the Middle Ages in historical change. Quedlinburg and Speyer, Königsfelden, Wiener Neustadt and Andernach, Berlin 2012 (= StiftungsGeschichte, vol. 8).

Oexle, Otto Gerhard, Memoria und Memorialüberlieferung, in: Schmid, Karl / Wollasch, Joachim (eds.), Memoria. The Historical Testimonial Value of Liturgical Commemoration in the Middle Ages, Munich 1984, pp. 384 - 440.

Oexle, Otto Gerhard, Memoria und Memorialüberlieferung im frühen Mittelalter, in: Fenske, Lutz / Rösener, Werner / Zotz, Thomas (eds.), Institutionen, Kultur und Gesellschaft

in the Middle Ages. Studies in honour of Josef Fleckenstein on his 65th birthday, Sigmaringen 1984, pp. 70 - 95.

Oexle, Otto Gerhard, Art. Memoria, Memorialüberlieferung, in: LMA VI (2003), sp. 510 - 513

Reuling, Ulrich, Quedlinburg. Königspfalz - Reichsstift - Markt, in: Fenske, Lutz (ed.), Deutsche Königspfalzen. Contributions to their historical and archaeological research. Vol. 4: Palatinates - imperial estates - royal courts, Göttingen 1996, pp. 184 - 248.

Schmid, Karl / Wollasch, Joachim, The community of the living and the deceased in testimonies of the Middle Ages, in: FMSt 1 (1967), p. 365 - 405

Schmid, Karl / Wollasch, Joachim (eds.), Memoria. The historical testimonial value of liturgical commemoration in the Middle Ages, Munich 1984.

Voigtländer, Klaus, Die Stiftskirche zu Quedlinburg. History of its restoration and decoration, with a contribution by Hans Berger, Berlin 1989

Wagner, Wolfgang, The Prayer Commemoration of the Liudolfingers in the Mirror of Royal and Imperial Charters from Henry I to Otto III, in: ADipl. 40 (1994), pp. 1 - 78

Wäscher, Hermann, Die Baugeschichte der Burgen Quedlinburg, Stecklenberg und Lauenburg, Halle 1956 (= series of publications of the state gallery Moritzburg in Halle, vol. 10)

Wäscher, Hermann, The castle hill in Quedlinburg. Geschichte seiner Bauten bis zum ausgehenden 12. Jahrhundert nach den Ereignissen der Grabungen von 1938 bis 1942, Berlin 1959 (= Schriften des Instituts für Theorie und Geschichte der Baukunst).